Memphis entrepreneur and Catholic leader Eugene Magevney was born in

1798 in County Fermanagh, Ireland. He studied for the priesthood but

changed his mind and became a school teacher. In 1828 he immigrated to

the United States and settled in Memphis in 1833. Magevney supported

himself by teaching in a small private school, where he accepted land as

payment from cash-strapped families.

Within a few years, Magevney's land acquisitions had become large enough

to permit him to leave teaching and concentrate on real estate

development, where he made his fortune. Soon recognized as a community

leader, he served as an alderman and in 1848 led the fight to establish

public schools. Always ready to defend his fellow Irishmen, Magevney

wrote editorials in the local newspaper protesting the prejudice to

which they were subjected.

A devout Catholic, Magevney helped to establish the city's first

Catholic church and parochial school. In 1839 the first mass was

celebrated in Magevney's house on Adams Avenue, where the first marriage

(his own) and the first baptism (his daughter Mary) were also

celebrated. Magevney was also one of those responsible for the founding

of St. Peter's Catholic Church, located next to his house. In 1941 the

Magevney heirs donated the house to the City of Memphis. It is now part

of the Memphis Museum System and open to the public.

Source: tennesseeenxyxlopedia.com

Wednesday, January 31, 2018

The Memphis Parkway System

The Memphis Parkway System, locally known as the Parkway System, The Parkways, or simply by their individual names is a system of parkways that formed the original outer beltway around Memphis, Tennessee. They consist of South Parkway, East Parkway, and North Parkway. Designed by George Kessler, the Parkway System connects Martin Luther King Jr. Riverside Park with Overton Park. The system was put on the National Register of Historic Places on July 3, 1989.

In response to the yellow fever epidemic and in an attempt to

revitalize Memphis, the city's leaders decided to improve the city's

infrastructure, including improving sewer systems, creating public

utilities, and creating a system of parks connected by a system of

boulevards. Starting in 1897, several areas of land were annexed into

the city, along with the areas that now comprise the parks mentioned

above. These lands were purchased in 1901. In that same year, the city

selected George Kessler to lay out this new plan. Planning and

construction of the Lea's Woods tract of land (now known as Overton

Park) was started in 1902 and completed in the same year. The

development and construction of Wilderberger Farm (now known as Martin

Luther King Jr. Riverside Park) started in the same year, but finished a

year later in 1903.

The development and construction of what is now known as the Parkway System started in 1904. The project had been delayed due to a lawsuit stating the government was using its power of eminent domain incorrectly, but the Tennessee Supreme Court found in favor of the city. Instead of a winding system of meandering parkways, Kessler decided to create a rectangular border around the city of Memphis using some existing streets. South Parkway and East Parkway (originally Trezevant Street) were constructed first. North Parkway was originally known as Summer Avenue (the name still carried by the route as it continues east from the intersection of North and East Parkways). North Parkway was also known as Speedway. Kessler originally designed parts of the Parkway System to be straight portions of tree-lined avenues where car and carriage owners could race against each other. However, the city of Memphis ended this practice in 1910 and imposed a speed limit on the entire system. Today, the road's racing past can still be seen in the name of the Speedway Terrace Historical District along North Parkway near Watkins Street.

The entire parkway system was completed in 1906. After its completion, residential development along its route increased. Many cities in Tennessee used Memphis' park and parkway system as a model for their own urban planning. The Parkway System roughly marked the city's boundaries for many years to come and is still an important corridor in the city of Memphis.

South Parkway, after passing U.S. Highway 78 (Lamar Avenue), turns into East Parkway South. Temporarily, the route's name reverts to South Parkway East, as it turns eastbound and intersects with South Cooper St. and East McLemore Avenue. South Parkway East becomes East Parkway South once again at its intersection with Airways Boulevard and Spottswood Avenue. It also picks up the designation of State Route 277. East Parkway South continues north until it crosses under Union Avenue and (two blocks later) becomes East Parkway North. At this point, it picks up U.S. Highway 64, U.S. Highway 70, U.S. Highway 79, and U.S. Highway 72, in addition to keeping the SR 277 designation. When it passes Poplar Avenue, Hwy 72 goes to the east, but it picks up the State Route 57 designation. At this point, it passes to the east of Overton Park and intersects with Sam Cooper Boulevard.

When East Parkway meets North Parkway, it loses all of the above-mentioned U.S. highways to the east (Summer Avenue) and the state highways to the north (Trezevant Street). However North Parkway picks up the State Route 1 designation and is one of the only sections in the state to have this route signed. North Parkway continues west, crosses Interstate 40, and ends at U.S. Highway 51/State Route 3/State Route 14 (Danny Thomas Boulevard). The road continues west as A.W. Willis Avenue, crossing the Wolf River Harbor, and ending on Mud Island.

Except for the South Parkway West section, the entire system is divided by a large median containing several trees, most of them very large and mature, and sections of flowered landscaping. South Parkway has two lanes in each direction and bike/parking lanes along portions of it. East Parkways has three lanes in each direction (except for when the routes pass under other roadways, in which case each direction narrows to two lanes, and the four northbound lanes of East Parkway between Poplar and Sam Cooper). North Parkway had 3 lanes in each direction until the mid 2010s when bike/parking lanes were added between Manassas and West Drive. The entire system has a forty-mile-per-hour speed limit.

South Parkway Section

History;

Kessler's plan for Overton Park. North Parkway is to the north (labeled

Summer Avenue) and East Parkway is to the east (labeled Trezevant

Street).

The development and construction of what is now known as the Parkway System started in 1904. The project had been delayed due to a lawsuit stating the government was using its power of eminent domain incorrectly, but the Tennessee Supreme Court found in favor of the city. Instead of a winding system of meandering parkways, Kessler decided to create a rectangular border around the city of Memphis using some existing streets. South Parkway and East Parkway (originally Trezevant Street) were constructed first. North Parkway was originally known as Summer Avenue (the name still carried by the route as it continues east from the intersection of North and East Parkways). North Parkway was also known as Speedway. Kessler originally designed parts of the Parkway System to be straight portions of tree-lined avenues where car and carriage owners could race against each other. However, the city of Memphis ended this practice in 1910 and imposed a speed limit on the entire system. Today, the road's racing past can still be seen in the name of the Speedway Terrace Historical District along North Parkway near Watkins Street.

The entire parkway system was completed in 1906. After its completion, residential development along its route increased. Many cities in Tennessee used Memphis' park and parkway system as a model for their own urban planning. The Parkway System roughly marked the city's boundaries for many years to come and is still an important corridor in the city of Memphis.

Route Description;

Moving in a counter-clockwise direction from the southwest corner, the Parkway System starts at Martin Luther King Jr. Riverside Park. It crosses Interstate 55 next to the park and continues east. This portion, known as South Parkway West, is a four-lane undivided road through an industrial area with no boulevard median or landscaping. After crossing Interstate 240/Interstate 69, the section known as South Parkway East becomes divided with a wooded boulevard median, like the majority of the parkways.South Parkway, after passing U.S. Highway 78 (Lamar Avenue), turns into East Parkway South. Temporarily, the route's name reverts to South Parkway East, as it turns eastbound and intersects with South Cooper St. and East McLemore Avenue. South Parkway East becomes East Parkway South once again at its intersection with Airways Boulevard and Spottswood Avenue. It also picks up the designation of State Route 277. East Parkway South continues north until it crosses under Union Avenue and (two blocks later) becomes East Parkway North. At this point, it picks up U.S. Highway 64, U.S. Highway 70, U.S. Highway 79, and U.S. Highway 72, in addition to keeping the SR 277 designation. When it passes Poplar Avenue, Hwy 72 goes to the east, but it picks up the State Route 57 designation. At this point, it passes to the east of Overton Park and intersects with Sam Cooper Boulevard.

When East Parkway meets North Parkway, it loses all of the above-mentioned U.S. highways to the east (Summer Avenue) and the state highways to the north (Trezevant Street). However North Parkway picks up the State Route 1 designation and is one of the only sections in the state to have this route signed. North Parkway continues west, crosses Interstate 40, and ends at U.S. Highway 51/State Route 3/State Route 14 (Danny Thomas Boulevard). The road continues west as A.W. Willis Avenue, crossing the Wolf River Harbor, and ending on Mud Island.

Except for the South Parkway West section, the entire system is divided by a large median containing several trees, most of them very large and mature, and sections of flowered landscaping. South Parkway has two lanes in each direction and bike/parking lanes along portions of it. East Parkways has three lanes in each direction (except for when the routes pass under other roadways, in which case each direction narrows to two lanes, and the four northbound lanes of East Parkway between Poplar and Sam Cooper). North Parkway had 3 lanes in each direction until the mid 2010s when bike/parking lanes were added between Manassas and West Drive. The entire system has a forty-mile-per-hour speed limit.

A section of the median of East Parkway was designated "Flowering Tree Trail" in 1956/57.

Landmarks:

Below is a list of landmarks within close proximity of the parkways.South Parkway Section

- President's Island / McKellar Lake

- M.L.K. Riverside Park

- Cooper-Young, Memphis

- Christian Brothers University

- Children's Museum of Memphis

- Mid-South Coliseum

- Liberty Bowl Memorial Stadium

- Memphis Theological Seminary

- Memphis Brooks Museum of Art

- Overton Park

Monday, November 20, 2017

Hill And Grosvenor Family Papers, 1860-1952

The Hill and Grosvenor families of Memphis, Tenn.,

were joined by the marriage of

Olivia Polk Hill (1861-1934) and Charles Niles

Grosvenor (1850-1931) in 1885. Olivia

Polk Hill Grosvenor's father, Napoleon Hill

(1830-1909), made his fortune during the

California gold rush and upon his return to

Memphis, married Mary Martin Wood, daughter

of a large planter. Hill then established a series

of firms in Memphis, culminating

in the formation of Hill Fontaine and Co., a large

inland cotton house.

In 1897, Charles Niles Grosvenor and Olivia Hill Grosvenor moved to El Paso, Tex., for his health.

The three Grosveor children, Phoebe Olivia (d. 1963), Charles Niles, Jr. (1890-1930), and Napoleon Hill, remained in Memphis. Apparently in 1902, Olivia Hill Grosvenor moved back to Memphis, followed by her husband in 1903. The Grosvenors spent much of their later years in Pass Christian, Miss. Primarily family correspondence, especially love letters between Olivia Polk Hill and Charles Niles Grosvenor, 1874-1885; Phoebe Olivia Grosvenor and Marion G. Evans and other suitors, 1908-1919; and Phoebe Airey Evans and Jack Petree, 1940-1942. Also included are letters, 1890- 1891, from Frank F. Hill about life at the University of the South, where he was in school; a letter, 1890, from Hamlin Garland; letters reflecting on life in El Paso, Tex., 1897-1902; and letters from students at Georgia Tech and Washington and Lee University, circa 1908-1910. Other papers include financial and legal materials of the Hill and Grosvenor families; poems and other writings; four diary volumes, 1892-1915, of Mary Martin Hill (1835-1922) dealing with family and personal news in Memphis and other locations; items relating to social life in Memphis, Tenn., 1895- 1940; material relating to Army Air Force training during World War II; and maps, 1897-1899, of mines in Chihuahua, Mexico.

Source: finding-aids.lib.unc.edu

In 1897, Charles Niles Grosvenor and Olivia Hill Grosvenor moved to El Paso, Tex., for his health.

The three Grosveor children, Phoebe Olivia (d. 1963), Charles Niles, Jr. (1890-1930), and Napoleon Hill, remained in Memphis. Apparently in 1902, Olivia Hill Grosvenor moved back to Memphis, followed by her husband in 1903. The Grosvenors spent much of their later years in Pass Christian, Miss. Primarily family correspondence, especially love letters between Olivia Polk Hill and Charles Niles Grosvenor, 1874-1885; Phoebe Olivia Grosvenor and Marion G. Evans and other suitors, 1908-1919; and Phoebe Airey Evans and Jack Petree, 1940-1942. Also included are letters, 1890- 1891, from Frank F. Hill about life at the University of the South, where he was in school; a letter, 1890, from Hamlin Garland; letters reflecting on life in El Paso, Tex., 1897-1902; and letters from students at Georgia Tech and Washington and Lee University, circa 1908-1910. Other papers include financial and legal materials of the Hill and Grosvenor families; poems and other writings; four diary volumes, 1892-1915, of Mary Martin Hill (1835-1922) dealing with family and personal news in Memphis and other locations; items relating to social life in Memphis, Tenn., 1895- 1940; material relating to Army Air Force training during World War II; and maps, 1897-1899, of mines in Chihuahua, Mexico.

Source: finding-aids.lib.unc.edu

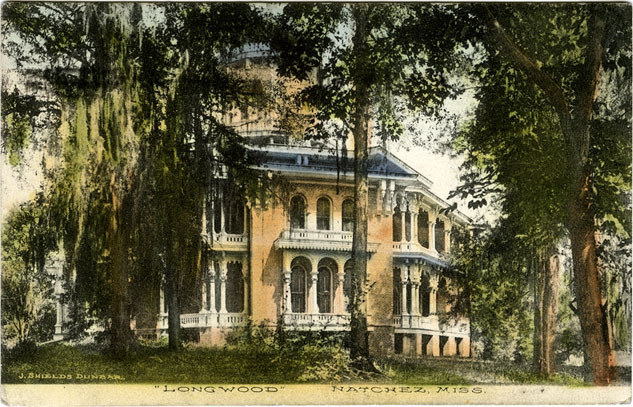

Longwood Plantation In Natchez, Mississippi

a pictorial by Bill Pitts

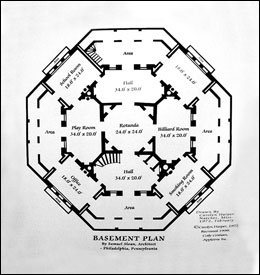

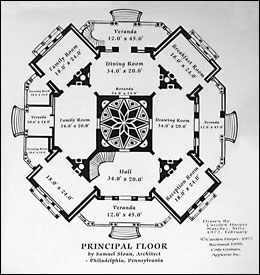

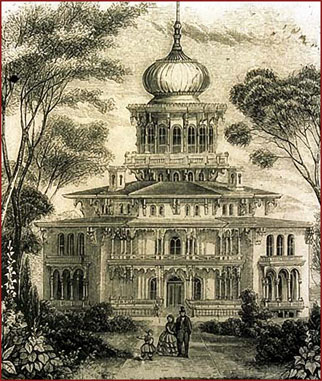

Longwood was built by Haller Nutt in 1860 as a home for himself, his wife, and their eight children. This 19th Century Oriental Style villa was to have been one of the grandest houses in the Natchez, Mississippi area. Architect Samuel Sloan of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania was hired to design the house in 1859, but work was left unfinished with the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861. In April of that year, the news of the beginning of the war reached the Natchez area, and the Philadelphia artisans dropped their tools and returned north to join the Union forces.

Although he was a Union sympathizer, Nutt lost his fortune as a result of the war and died in 1864 of pneumonia — although some claim it was of a broken heart over the lost dream of his magnificent Longwood.

Longwood has been designated a Registered National Historic Landmark, a Mississippi Landmark, and an historic site on the Civil War Discovery Trail.

Photos by Bill Pitts, unless otherwise noted.

Presented to the Pilgrimage Garden Club of Natchez by the Kelly E. McAdams Foundation of Austin, Texas in 1970 (in order to read the plaques above, click for a larger image), Longwood is the largest octagonal house in the country and a fine example of the Oriental Revival style that was popular in the mid-19th century. Samuel Sloan "was a leading Philadelphia-based architect and writer of architecture books . . . . He specialized in Italianate villas and country houses, churches, and institutional buildings." [See Wikipedia article on Sloan and this biography] Of his many projects, Longwood is his most well-known.

In 1963, two of Haller's and Julia's grandchildren, Mrs. Robert Blanchard and Mrs. Leslie K. Pollard, along with Mrs. Singleton Gardner who was the widow of Jim Ward, another grandchild, sold Longwood to Kelly Edgar and Ina May Ogletree McAdams, "who have long held an abiding interest in the preservation of all early Americana, and more especially in the protection and saving for prosterity those structures of great historic and architectural importance to be found in our country." (from The Legend of Longwood by Margaret S. Hendrix, Natchez, Mississippi)

Derisively referred to in Natchez as "Nutt's Folly," Longwood can be seen (above, left) in this romanically inspired engraving that appeared at the beginning of the chapter titled "Oriental Villa" in Sloan's book, Homestead Architecture, and in a photograph taken by James Butters on April 14, 1936 for the Library of Congresses' Historic American Buildings Survey (above, right). Note the roof of the detached kitchen to the left of the house in the photograph and two of the four chimneys on the roof on either side of the domed cupola. In spite of the derisive comments of Haller Nutt's neighbors, the building is impressive and definitely one of a kind.

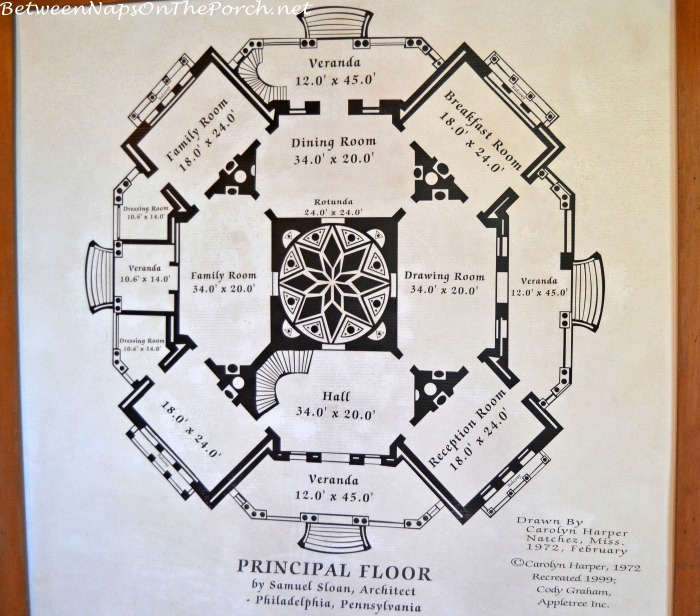

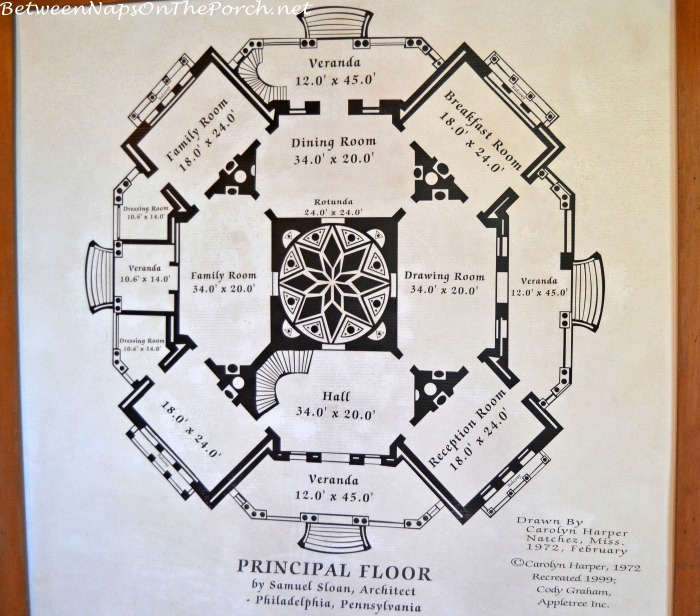

The completed house was to have had 32 rooms, 26 fireplaces, 115 doors, 96 columns, and a total of 30,000 square feet of living space, but only nine of the 32 rooms were finished.

Click here to see a cross-section of Longwood.

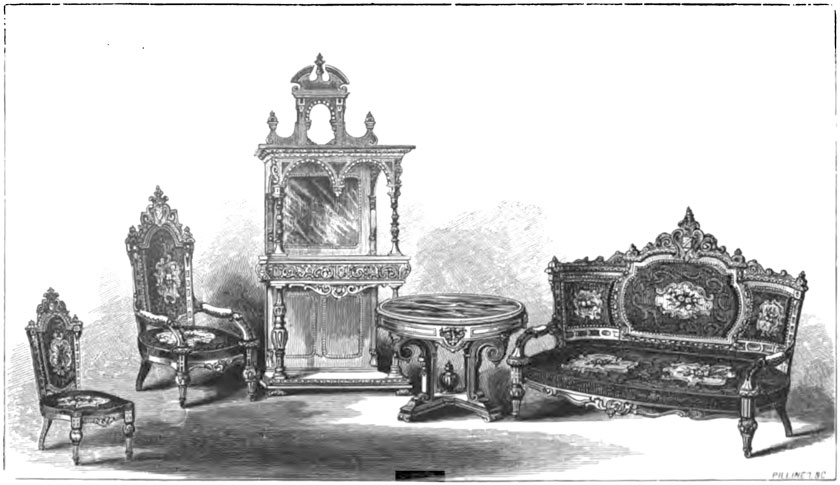

Furnishings for the house were purchased in countries across Europe and shipped across the Atlantic for eventual delivery up the Mississippi River by steamboat to Natchez.

The final leg of this journey would have been by wagon from Natchez Under the Hill to Longwood but the outbreak of the Civil War led to the shipments being seized in route by the Federal Blockade of the Southern ports. Reportedly, some of these shipments found their way to various museums.

The more than one million bricks used to build Longwood (as seen at left) were all made on the grounds of the estate.

In his book Homestead Architecture, Samuel Sloan estimated that the cost of a house such as Longwood "would not vary much from $55,000," the equivalent of $1,300,000 in 2006 according to the websiteMeasuringWorth.

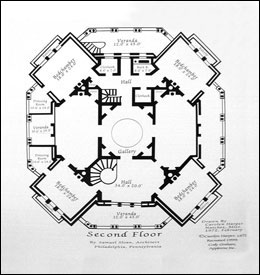

These three reproductions of the structure's floor plans, on display at Longwood, clearly show the octagonal shape of the house and the intended use for the various rooms. Click on each for a larger view of that plan. Please use these plans as a guide for visualizing the location of the rooms shown here. Orders for furniture went to New Orleans, New York, and Philadelphia. Orders for marble statues, marble mantles, and tiles went to Italy.

Meant to be the gentlemen’s smoking room in the basement, this bedroom (above, left) includes a toilet disguised as a brown chair (seen to the right of the bed). Next to the intended smoking room was to be the billiard room (above, right), now the family’s music room.

This engraving from Sloan's book Homestead Architecture shows the style of furniture that had been meant for the Nutt's drawing room. As railroad shipments from the north were out of the question during the Civil War, the suite of furniture was sold instead to railroad magnate Asa Packer and can be found today in the parlor of his mansion in Jim Thorpe, Pennsylvania.

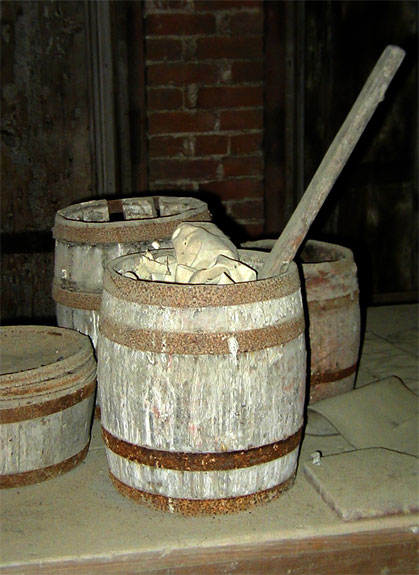

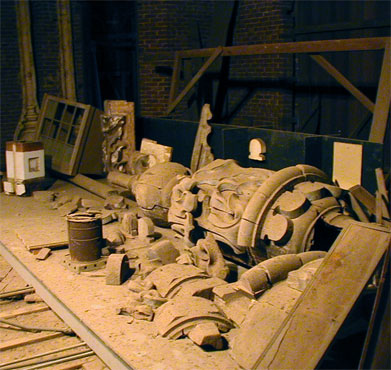

The crate that protected the Stieff grand piano (above, left) on its sea voyage from the Stieff factory in Baltimore, Maryland still sits upstairs on the unfinished main floor (above, right) with the dust of a century and a half heavy upon it.

More dust covered items found in the unfinished area of the house (above) are these trunks and tubs, containers and barrels undoubtedly used by the builders of Longwood, and this empty shipping crate from Park Avenue in New York City that is clearly marked with the address of daughter Julia Nutt, who lived on — unmarried — at Longwood until her death in 1932.

One of the unfinished rooms on the main floor (above, left) showing the boarded-up windows that are seen from the outside. The original 24-foot tall wooden finial (lying on its side above, center) was replaced with a fiberglass replica, now atop the sixteen-sided cupola’s Byzantine-Moorish, onion-shaped dome (above, right). Note the modern, cube-shaped mold (seen at the extreme left of the center photo) that was used to form the parts of this new finial.

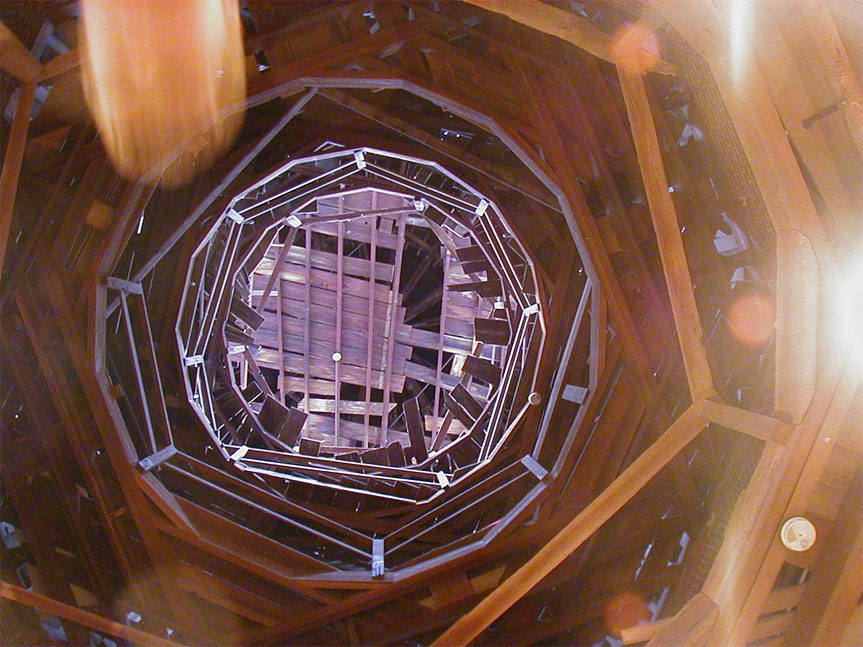

A system of mirrors had been designed to reflect sunlight to the many rooms of Longwood from the windows in the sixteen-sided tower atop the house. The view above of the interior of this high cupola, taken in a time-lapse from the unfinished second floor, shows the blurs of people passing over the camera that is sitting facing up on the floor. The chimney-like shape of the house was intended to funnel warm air up toward the top of the cupola, creating an updraft that escaped through windows high in the building, thus drawing fresh air into the lower floors.

Haller Nutt and his family settled in the basement, thinking the war would be over in a few months and that work on the house could then resume (basement exterior shown at upper left with retaining wall). Nutt’s descendants went on to occupy the unfinished house for the next 100 years, before it was presented to the Pilgrimage Garden Club of Natchez in 1970. The stairs shown in the photo to the right lead from the basement hall up to the first floor.

Heat was to be supplied by the 26 fireplaces arranged throughout the living areas. This plate warmer (above, center) was placed in front of the fireplace in the dining room to keep food hot prior to serving. A modern electic heater stands in front of the fireplace in the right-hand photograph.

Furniture miniatures (above, center), left behind by salesmen as samples of their wares, became toys for the Nutt children, two of whom can be seen in this painting (above, left). The portrait of the unknown lady (above, right) was revealed when a landscape painting was sent out to be cleaned and the landscape washed away. She has not been identified as a family member.

Although life in the unfinished mansion during the years of the Civil War would have had its hardships, the family was able to maintain a comfortable existence with the furnishings that they had on hand (above, left). The Indian-style punkah, or “shoo fly” fan (above, center), made dining more comfortable, for young (above, right) and older family members alike.

The carriage house in back of the main house (above, left) shelters — you guessed it — Julia Nutt's carriage (above, right).

Fine architectural details grace the many balconies of Longwood (above).

Separated from Longwood by a small stand of oak trees (above, left) stands the servants' quarters, a three-story, 12-room building that was built before construction of Longwood began (above, center). It would serve as the family's home until the main house could be completed. It appears to be a two-story structure but is built on a slope so that the second floor is level with the drive (above, right).

Black & white photo by Patricia Heintzelman, Historic Sites Survey, National Park Service, 1975

Postcard courtesy of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History

Commemorated on this hand-colored postcard (above), Longwood stands today as an iconic symbol of the Old South.

Click the thumbnails below for more postcards courtesy of Anna James, manager of Longwood.

Longwood is located at 140 Lower Woodville Road in Natchez, Mississippi.

Longwood is open daily, except Thanksgiving Day, Christmas Eve and Christmas Day.

Hours of operation are subject to seasonal changes.

For more information on Longwood’s location and hours of operation, call 601/442-5193.

Longwood is open daily, except Thanksgiving Day, Christmas Eve and Christmas Day.

Hours of operation are subject to seasonal changes.

For more information on Longwood’s location and hours of operation, call 601/442-5193.

External Link: betweennapsontheporch.net

Source: newsouthernview.com

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)