New Orleans (pronounced /nʲuːˈɔrliənz, nʲuːˈɔrlənz/; French: La Nouvelle-Orléans [lanuvɛlɔʀleɑ̃] (help·info)) is a major United States port city. From its founding until Hurricane Katrina devastated the city in 2005, New Orleans was the largest city in the U.S. state of Louisiana, but because of the large number of residents who have left due to Katrina, Baton Rouge is currently slightly more populous. New Orleans is the center of the Greater New Orleans metropolitan area, which remains the largest metro area in the state.

New Orleans City Seal

New Orleans City SealNew Orleans is located in southeastern Louisiana, straddling the Mississippi River. It is coextensive with Orleans Parish, meaning that the boundaries of the city and the parish are the same. It is bounded by the parishes of St. Tammany (north), St. Bernard (east), Plaquemines (south), and Jefferson (south and west). Lake Pontchartrain, part of which is included in the city limits, lies to the north, and Lake Borgne lies to the east.

The city is named after Philippe II, Duc d'Orléans, Regent of France, and is one of the oldest cities in the United States.

Philippe Charles of Orléans, Duke of Orléans (Philippe d'Orléans, duc d'Orléans) (August 2, 1674 – December 2, 1723), was a member of the House of Orléans - a cadet branch of the Royal House of France. At the death of his uncle king Louis XIV, he became the Regent during the minority of the new young king Louis XV, from 1715 to 1723, an era known as the Regency. He assembled the Orléans Collection, one of the finest collections of paintings ever made by a non-monarch.

It is well known for its multicultural and multilingual heritage, cuisine, architecture, music (particularly as the birthplace of jazz), and its annual Mardi Gras and other celebrations and festivals. The city is often referred to as the "most unique" city in America.

Revelers, Frenchmen Street, Faubourg Marigny

Revelers, Frenchmen Street, Faubourg MarignyMardi Gras in New Orleans, Louisiana is one of the most famous Carnival celebrations in the world.

The New Orleans Carnival season, with roots in the start of the Catholic season of Lent, starts on Twelfth Night (January 6). The season of parades, balls (some of them masquerade balls), and king cake parties begins on that date.

From about two weeks before, through Fat Tuesday, there is at least one major parade each day. The largest and most elaborate parades take place the last five days of the season. In the final week of Carnival many events large and small occur throughout New Orleans and surrounding communities.

The parades in New Orleans are organized by Carnival krewes. Krewe float riders toss throws to the crowds; the most common throws are strings, usually made of plastic colorful beads, doubloons (aluminium or wooden dollar-sized coins usually impressed with a krewe logo), decorated plastic throw cups, and small inexpensive toys. Major krewes follow the same parade schedule and route each year.

While many tourists center their Mardi Gras season activities on Bourbon Street and the French Quarter, none of the major Mardi Gras parades have entered the Quarter since 1972 because of its narrow streets and overhead obstructions. Instead, major parades originate in the Uptown and Mid-City districts and follow a route along St. Charles Avenue and Canal Street, on the upriver side of the French Quarter.

To New Orleanians, "Mardi Gras" refers only to the final and most elaborate day of the Carnival Season; visitors tend to refer to the entire Carnival as "Mardi Gras." Some locals have thus started to refer to the final day of Carnival as "Mardi Gras Day" to avoid confusion.

Costumed musicians, French Quarter, New Orleans

Costumed musicians, French Quarter, New Orleans"Mardi Gras" (French for Fat Tuesday) is the day before Ash Wednesday. Mardi Gras is the final day of Carnival, the three-day period preceding the beginning of Lent, the Sunday, Monday, and Tuesday immediately before Ash Wednesday (some traditions count Carnival as the entire period of time between Epiphany or Twelfth Night and Ash Wednesday). The entire three-day period has come to be known in many areas as Mardi Gras. Perhaps the cities most famous for their Mardi Gras celebrations include Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, and New Orleans, Louisiana. Many other places have important Mardi Gras celebrations as well. Carnival is an important celebration in most of Europe, except in Ireland and the United Kingdom where pancakes are the tradition, and also in many parts of Latin America and the Caribbean.

Jazz,

Jazz is an American musical art form which originated in the beginning of the 20th century in African American communities in the Southern United States from a confluence of African and European music traditions. The style's West African pedigree is evident in its use of blue notes, improvisation, polyrhythms, syncopation, and the swung note.

From its early development until the present, jazz has also incorporated music from 19th and 20th century American popular music. The word jazz began as a West Coast slang term of uncertain derivation and was first used to refer to music in Chicago in about 1915; for the origin and history, see Jazz (word).

Jazz has, from its early 20th century inception, spawned a variety of subgenres, from New Orleans Dixieland dating from the early 1910s, big band-style swing from the 1930s and 1940s, bebop from the mid-1940s, a variety of Latin jazz fusions such as Afro-Cuban and Brazilian jazz from the 1950s and 1960s, jazz-rock fusion from the 1970s and late 1980s developments such as acid jazz, which blended jazz influences into funk and hip-hop.

Definition

Double bassist Reggie Workman, tenor saxophone player Pharoah Sanders, and drummer Idris Muhammad performing in 1978

Double bassist Reggie Workman, tenor saxophone player Pharoah Sanders, and drummer Idris Muhammad performing in 1978Jazz can be hard to define because it spans from Ragtime waltzes to 2000s-era fusion. While many attempts have been made to define jazz from points of view outside jazz, such as using European music history or African music, jazz critic Joachim Berendt argues that all such attempts are unsatisfactory. One way to get around the definitional problems is to define the term “jazz” more broadly. Berendt defines jazz as a "form of art music which originated in the United States through the confrontation of blacks with European music"; he argues that jazz differs from European music in that jazz has a "special relationship to time, defined as 'swing'", "a spontaneity and vitality of musical production in which improvisation plays a role"; and "sonority and manner of phrasing which mirror the individuality of the performing jazz musician".

Travis Jackson has also proposed a broader definition of jazz which is able to encompass all of the radically different eras: he states that it is music that includes qualities such as "swinging', improvising, group interaction, developing an 'individual voice', and being 'open' to different musical possibilities". Krin Gabbard claims that “jazz is a construct” or category that, while artificial, still is useful to designate “a number of musics with enough in common part of a coherent tradition”.

While jazz may be difficult to define, improvisation is clearly one of its key elements. Early blues was commonly structured around a repetitive call-and-response pattern, a common element in the African American oral tradition. A form of folk music which rose in part from work songs and field hollers of rural Blacks, early blues was also highly improvisational. These features are fundamental to the nature of jazz. While in European classical music elements of interpretation, ornamentation and accompaniment are sometimes left to the performer's discretion, the performer's primary goal is to play a composition as it was written.

In jazz, however, the skilled performer will interpret a tune in very individual ways, never playing the same composition exactly the same way twice. Depending upon the performer's mood and personal experience, interactions with fellow musicians, or even members of the audience, a jazz musician/performer may alter melodies, harmonies or time signature at will. European classical music has been said to be a composer's medium. Jazz, however, is often characterized as the product of democratic creativity, interaction and collaboration, placing equal value on the contributions of composer and performer, 'adroitly weigh[ing] the respective claims of the composer and the improviser'.

In New Orleans and Dixieland jazz, performers took turns playing the melody, while others improvised countermelodies. By the swing era, big bands were coming to rely more on arranged music: arrangements were either written or learned by ear and memorized - many early jazz performers could not read music. Individual soloists would improvise within these arrangements. Later, in bebop the focus shifted back towards small groups and minimal arrangements; the melody (known as the "head") would be stated briefly at the start and end of a piece but the core of the performance would be the series of improvisations in the middle. Later styles of jazz such as modal jazz abandoned the strict notion of a chord progression, allowing the individual musicians to improvise even more freely within the context of a given scale or mode. The avant-garde and free jazz idioms permit, even call for, abandoning chords, scales, and rhythmic meters.

Origins

In the late 18th-century painting The Old Plantation, African-Americans dance to banjo and percussion.

In the late 18th-century painting The Old Plantation, African-Americans dance to banjo and percussion.By 1808 the Atlantic slave trade had brought almost half a million Africans to the United States. The slaves largely came from West Africa and brought strong tribal musical traditions with them. Lavish festivals featuring African dances to drums were organized on Sundays at Place Congo, or Congo Square, in New Orleans until 1843, as were similar gatherings in New England and New York. African music was largely functional, for work or ritual, and included work songs and field hollers. In the African tradition, they had a single-line melody and a call-and-response pattern, but without the European concept of harmony. Rhythms reflected African speech patterns, and the African use of pentatonic scales led to blue notes in blues and jazz.

The blackface Virginia Minstrels in 1843, featuring tambourine, fiddle, banjo and bones.

The blackface Virginia Minstrels in 1843, featuring tambourine, fiddle, banjo and bones.In the early 19th century an increasing number of black musicians learned to play European instruments, particularly the violin, which they used to parody European dance music in their own cakewalk dances. In turn, European-American minstrel show performers in blackface popularized such music internationally, combining syncopation with European harmonic accompaniment. Louis Moreau Gottschalk adapted African-American cakewalk music, South American, Caribbean and other slave melodies as piano salon music. Another influence came from black slaves who had learned the harmonic style of hymns and incorporated it into their own music as spirituals.

The origins of the blues are undocumented, though they can be seen as the secular counterpart of the spirituals. Paul Oliver has drawn attention to similarities in instruments, music and social function to the griots of the West African savannah.

Ragtime

Scott Joplin.

Scott Joplin.Emancipation of slaves led to new opportunities for education of freed African-Americans, but strict segregation meant limited employment opportunities. Black musicians provided "low-class" entertainment at dances, minstrel shows, and in vaudeville, and many marching bands formed. Black pianists played in bars, clubs and brothels, and ragtime developed.

Ragtime appeared as sheet music with the African American entertainer Ernest Hogan's hit songs in 1895, and two years later Vess Ossman recorded a medley of these songs as a banjo solo "Rag Time Medley". Also in 1897, the white composer William H. Krell published his "Mississippi Rag" as the first written piano instrumental ragtime piece. The classically-trained pianist Scott Joplin produced his "Original Rags" in the following year, then in 1899 had an international hit with "Maple Leaf Rag." He wrote numerous popular rags combining syncopation, banjo figurations and sometimes call-and-response, which led to the ragtime idiom being taken up by classical composers including Claude Debussy and Igor Stravinsky. Blues music was published and popularized by W. C. Handy, whose "Memphis Blues" of 1912 and "St. Louis Blues" of 1914 both became jazz standards.

New Orleans music,

The Bolden Band around 1905.

The Bolden Band around 1905.The music of New Orleans had a profound effect on the creation of early jazz. Many early jazz performers played in the brothels and bars of red-light district around Basin Street called "Storyville." In addition, numerous marching bands played at lavish funerals arranged by the African American community. The instruments used in marching bands and dance bands became the basic instruments of jazz: brass and reeds tuned in the European 12-tone scale and drums. Small bands of primarily self-taught African American musicians, many of whom came from the funeral-procession tradition of New Orleans, played a seminal role in the development and dissemination of early jazz, traveling throughout Black communities in the Deep South and, from around 1914 on, Afro-Creole and African American musicians playing in vaudeville shows took jazz to western and northern US cities.

Morton published "Jelly Roll Blues" in 1915, the first jazz work in print.

Morton published "Jelly Roll Blues" in 1915, the first jazz work in print.Afro-Creole pianist Jelly Roll Morton began his career in Storyville. From 1904, he toured with vaudeville shows around southern cities, also playing in Chicago and New York. His "Jelly Roll Blues," which he composed around 1905, was published in 1915 as the first jazz arrangement in print, introducing more musicians to the New Orleans style. In the northeastern United States, a "hot" style of playing ragtime had developed, notably James Reese Europe's symphonic Clef Club orchestra in New York which played a benefit concert at Carnegie Hall in 1912, and his "Society Orchestra" which in 1913 became the first black group to make Jazz recordings. The Baltimore rag style of Eubie Blake influenced James P. Johnson's development of "Stride" piano playing, in which the right hand plays the melody, while the left hand provides the rhythm and bassline.

The Original Dixieland Jass Band's "Livery Stable Blues" released early in 1917 is one of the early jazz records. That year numerous other bands made recordings featuring "jazz" in the title or band name, mostly ragtime or novelty records rather than jazz. In September 1917 W.C. Handy's Orchestra of Memphis recorded a cover version of "Livery Stable Blues". In February 1918 James Reese Europe's "Hellfighters" infantry band took ragtime to Europe during World War I, then on return recorded Dixieland standards including "The Darktown Strutter's Ball".

Nickname(s): "The Crescent City," "The Big Easy," "The City That Care Forgot," "Nawlins," and "NOLA" (acronym for New Orleans, LA).

Aerial Map of Lake Pontchartrain

Aerial Map of Lake PontchartrainLake Pontchartrain (pronounced /ˈpɒntʃətreɪn/ in English; Lac Pontchartrain, IPA [lak pɔ̃ʃaʀtʀɛ̃] (help·info) in French) is a brackish lake located in southeastern Louisiana. It is the second-largest saltwater lake in the United States, after the Great Salt Lake in Utah, and the largest lake in Louisiana. It covers an area of 630 square miles (1630 square km) with an average depth of 12 to 14 feet (about 4 meters). Some shipping channels are kept deeper through dredging. It is roughly oval in shape, about 40 miles (64 km) wide and 24 miles (39 km) from south to north.

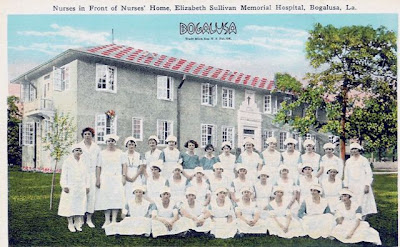

The south shore forms the northern boundary of the city of New Orleans, and its two largest suburbs Metairie and Kenner. On the north shore of Lake Pontchartrain is an area called the North Shore or Northshore or the Northlake area. It is composed of cities such as Mandeville, Covington, Abita Springs, Madisonville, Slidell; in Saint Tammany Parish; Ponchatoula, Hammond, and Amite in Tangipahoa Parish; and Franklinton and Bogalusa in Washington Parish. These Northshore parishes form the eastern Florida Parishes.

Namesake,

Lake Pontchartrain is named for Louis Phélypeaux, comte de Pontchartrain, the French Minister of the Marine, Chancellor of France and Controller-General of Finances during the reign of France's "Sun King," Louis XIV, for whom Louisiana is named.

Description,

Lake Pontchartrain is not a true lake but an estuary connected to the Gulf of Mexico via the Rigolets strait (known locally as "the Rigolets") and Chef Menteur Pass into Lake Borgne, another large lagoon, and therefore experiences small tidal changes. It receives fresh water from the Tangipahoa, Tchefuncte, Tickfaw, Amite, and Bogue Falaya Rivers, and from Bayou Lacombe and Bayou Chinchuba.

Salinity varies from negligible at the northern cusp west of Mandeville up to nearly half the salinity of seawater at its eastern bulge near Interstate 10. Lake Maurepas, a true fresh water lake, connects with Lake Pontchartrain on the west via Pass Manchac. The Industrial Canal connects the Mississippi River with the lake at New Orleans. Bonnet Carré Spillway diverts water from the Mississippi into the lake during times of river flooding.

History,

The lake was created 2,600 to 4,000 years ago as the evolving Mississippi River Delta formed its southern and eastern shorelines with alluvial deposits. Its Native American name was Okwata ("Wide Water"). In 1699, French explorer Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville renamed it Pontchartrain after Louis Phélypeaux, comte de Pontchartrain.

Lake Pontchartrain at New Orleans during Hurricane Georges in 1998; lakefront camps outside of the protection levee suffered severe damage.

Lake Pontchartrain at New Orleans during Hurricane Georges in 1998; lakefront camps outside of the protection levee suffered severe damage.Human habitation of the region began at least 3,500 years ago, but increased rapidly with the arrival of Europeans about 300 years ago. The current population is over 1.5million. The United States Geological Survey is monitoring the environmental effects of shoreline erosion, loss of wetlands, pollution from urban areas and agriculture, saltwater intrusion from artificial waterways, dredging, basin subsidence and faulting, storms and sea-level rise, and freshwater diversion from the Mississippi and other rivers.

New Orleans,

New Orleans was established at a Native American portage between the Mississippi River and Lake Pontchartrain. The lake provides numerous recreational activities for people in New Orleans and is also home to the Southern Yacht Club. In the 1920s the Industrial Canal in the eastern part of the city opened, providing a direct navigable water connection, with locks, between the Mississippi River and the lake. In the same decade, a project dredging new land from the lake shore behind a new concrete floodwall began; this would result in an expansion of the city into the former swamp between Metairie/Gentilly Ridges and the lakefront. The Lake Pontchartrain Causeway was constructed in the 1950s and 1960s, connecting New Orleans (by way of Metairie) with Mandeville and bisecting the lake in a north-northeast line. At 24 miles (39 km), the Causeway is the longest bridge over a body of water in the world.

Hurricanes

During hurricanes, a storm surge can build up in Lake Pontchartrain. Wind pushes water into the lake from the Gulf of Mexico as a hurricane approaches from the south, and from there it can spill into New Orleans.

A hurricane in September, 1947 flooded much of Metairie, Louisiana, much of which is slightly below sea level due to land subsidence after marshland was drained. After the storm, hurricane-protection levees were built along Lake Pontchartrain's south shore to protect New Orleans and nearby communities. A storm surge of 10 feet (3 m) from Hurricane Betsy overwhelmed some levees in Eastern New Orleans in 1965 (while storm surge funneled in by the Mississippi River Gulf Outlet Canal and a levee failure flooded most of the Lower 9th Ward). After this the levees encircling the city and outlying parishes were raised to heights of 14 to 23 feet (4-7 m). Due to cost concerns, the levees were built to protect against only a Category 3 hurricane; however, some of the levees initially withstood the Category 5 storm surge of Hurricane Katrina (August 2005), which only slowed to Category 3 winds within hours of landfall (due to a last-minute eyewall replacement cycle).

Experts using computer modeling at Louisiana State University subsequent to Hurricane Katrina have concluded that the levees were never topped but rather faulty design, inadequate construction, or some combination of the two were responsible for the flooding of most of New Orleans: some canal walls leaked underneath because the wall foundations were not deep enough in peat-subsoil to withstand the pressure of higher water.

Hurricane Katrina

Windspeed of Hurricane Katrina 7 a.m., showng hurricane-force winds (yellow/brown/red: 75-92 mph) hitting the northeast/south shores of Lake Pontchartrain (1 hour after landfall) on 29-Aug-2005.

Windspeed of Hurricane Katrina 7 a.m., showng hurricane-force winds (yellow/brown/red: 75-92 mph) hitting the northeast/south shores of Lake Pontchartrain (1 hour after landfall) on 29-Aug-2005.  Windspeed of Hurricane Katrina 10 a.m., showing hurricane-force winds (yellow/brown) still hitting the north/southeast shores of Lake Pontchartrain (4 hours after landfall)

Windspeed of Hurricane Katrina 10 a.m., showing hurricane-force winds (yellow/brown) still hitting the north/southeast shores of Lake Pontchartrain (4 hours after landfall)When Hurricane Katrina reached Category 5 in 2005, some experts predicted that the levee system might fail completely if the storm passed close to the city. Although Katrina weakened to a Category 3 before making landfall on August 29 (with only Category 1-2 strength winds in New Orleans on the weaker side of the eye of the hurricane), the outlying New Orleans East along south Lake Pontchartrain was in the eyewall with winds, preceding the eye, nearly as strong as Bay St. Louis, MS. Canals near Chalmette began leaking at 8 am,[citation needed] and some levees/canals, designed to withstand Category 3 storms, suffered multiple breaks the following day (see Effect of Hurricane Katrina on New Orleans), flooding 80% of the city.

The walls of the Industrial Canal were breached by storm surge via the Mississippi River Gulf Outlet, while the 17th Street Canal and London Avenue Canal experienced catastrophic breaches, even though water levels never topped their flood walls. Louisiana State University experts presented evidence that some of these structures might have had design flaws or faulty construction.

There are indications that the soft earth and peat underlying canal walls may have given way. In the weeks before Katrina, tests of salinity in seepage pools near canals showed them to be lake water, not fresh water from broken mains. The 5.5 mile (9 km) long I-10 Twin Span Bridge heading northeast between New Orleans and Slidell was destroyed. The shorter Fort Pike Bridge crossing the outlet to Lake Borgne remained intact.

Much of the northern sector of the suburban areas of Metairie and Kenner was flooded with up to 2-3 feet of water. In this area, flooding was not the result of levee overtopping, but was due to a decision by the governmental administration of Jefferson Parish to abandon the levee-aligned drainage pumping stations. This resulted in the reverse flow of lake water through the pumping stations into drainage canals which subsequently overflowed, causing extensive flooding of the area between I-10 and the lakefront. When the pump operators were returned to their stations, water was drained out of Metairie and Kenner in less than a day, in some cases, only a few hours.

On September 5, 2005, the Army Corps of Engineers started to fix levee breaches by dropping huge sandbags from Chinook helicopters. The London Avenue Canal and Industrial Canal were blocked at the lake as permanent repairs started. On September 6, the Corps began pumping flood water back into the lake after seven days in the streets of New Orleans. Because it was fouled with dead animals, sewage, heavy metals, petrochemicals, and other dangerous substances, the Army Corps worked with the US EPA and Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality (LDEQ) to avoid major contamination and eutrophication of the lake.

Aerial photography suggests that 25 billion gallons (95 bn liters) of water covered New Orleans as of September 2, which equals about 2% of Lake Pontchartrain's volume. Due to a lack of electricity, the city was unable to treat the water before pumping it into the lake. It is unclear how long the pollution will persist and what its environmental damage to the lake will be, or the hazards from the mold and contaminated mud remaining in the city.

On September 24, 2005, Hurricane Rita did not breach the temporary repairs in the main part of the city, but the repair on the Industrial Canal wall in the lower 9th ward was breached, allowing about 2 feet of water back into that neighborhood.

Lake Borgne [right center] is southeast of Lake Pontchartrain and east of New Orleans, Louisiana.

Lake Borgne [right center] is southeast of Lake Pontchartrain and east of New Orleans, Louisiana.Lake Borgne is a lagoon in eastern Louisiana of the Gulf of Mexico. Due to coastal erosion, it is no longer actually a lake but rather an arm of the Gulf of Mexico. Its name comes from the French word borgne, which means "one-eyed".

The three large lakes, Maurepas,Pontchartrain, and Borgne cover 55% of the Pontchartrain Basin. Lakes Maurepas and Pontchartrain are separated by land bridges of cypress swamp and fresh/intermediate marsh. A brackish marsh land bridge and Lake St. Catherine separate Lake Pontchartrain from Lake Borgne. The Rigolets and Chef Menteur Pass are the two open water connections between Pontchartrain and Borgne.

A strip of marsh separates MRGO (left) from Lake Borgne (right).

A strip of marsh separates MRGO (left) from Lake Borgne (right).Due to coastal erosion Borgne is now a lagoon connecting to the Gulf of Mexico, but early 18th century maps show it as a lake largely separated from the Gulf by a considerable extent of wetlands which have since disappeared.

The basin contains 483,390 acres (1956 km²) of wetlands, consisting of nearly 38,500 acres (156 km²) of fresh marsh, 28,600 acres (116 km²) of intermediate marsh, 116,800 acres (473 km²) of brackish marsh, 83,900 acres (340 km²) of saline marsh, and 215,600 acres (873 km²) of cypress swamp. Since 1932, more than 66,000 acres (267 km²) of marsh have converted to water in the Pontchartrain Basin — over 22% of the marsh that existed in 1932.

The primary causes of wetland loss in the basin are the interrelated effects of human activities and the estuarine processes that began to predominate many hundreds of years ago, as the delta was abandoned.

History,

Beginnings through the 19th century

Map of New Orleans from the 1888 Meyers Konversations-LexikonLa

Map of New Orleans from the 1888 Meyers Konversations-LexikonLaNouvelle-Orléans,

(New Orleans) was founded May 7, 1718, by the French Mississippi Company, under the direction of Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville on land inhabited by the Chitimacha. It was named for Philippe II, Duke of Orléans, who was Regent of France at the time; his title came from the French city of Orléans. The French colony was ceded to the Spanish Empire in the Treaty of Paris (1763) and remained under Spanish control until 1801, when it reverted to French control. Most of the surviving architecture of the Vieux Carré (French Quarter) dates from this Spanish period. Napoleon sold the territory to the United States in the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. The city grew rapidly with influxes of Americans, French, and Creole French. Major commodity crops of sugar and cotton were cultivated with slave labor on large plantations outside the city.

The Haitian Revolution of 1804 established the second republic in the Western Hemisphere and the first led by blacks. Haitian refugees both white and free people of color (affranchis) arrived in New Orleans, often bringing slaves with them. While Governor Claiborne and other officials wanted to keep out more free black men, French Creoles wanted to increase the French-speaking population. As more refugees were allowed in Louisiana, Haitian émigrés who had gone to Cuba also arrived. Nearly 90 percent of the new immigrants settled in New Orleans. The 1809 migration brought 2,731 whites; 3,102 free persons of African descent; and 3,226 enslaved refugees to the city, doubling its French-speaking population. Sixty-three percent of Crescent City inhabitants were now black, as Americans classified people.

A true-color satellite image of New Orleans taken on NASA's Landsat 7

A true-color satellite image of New Orleans taken on NASA's Landsat 7During the War of 1812, the British sent a force to conquer the city. The Americans decisively defeated the British troops, led by Sir Edward Pakenham, in the Battle of New Orleans on January 8, 1815.

As a principal port, New Orleans had the major role of any city during the antebellum era in the slave trade. Its port handled huge quantities of goods for export from the interior and import from other countries to be traded up the Mississippi River. The river was filled with steamboats, flatboats and sailing ships. At the same time, it had the most prosperous community of free persons of color in the South, who were often educated and middle-class property owners.

The population of the city doubled in the 1830s, and by 1840 New Orleans had become the wealthiest and third-most populous city in the nation. It had the largest slave market. Two-thirds of the more than one million slaves brought to the Deep South arrived via the forced migration of the internal slave trade. The money generated by sales of slaves in the Upper South has been estimated at fifteen percent of the value of the staple crop economy. The slaves represented half a billion dollars in property, and an ancillary economy grew up around the trade in slaves - for transportation, housing and clothing, fees, etc., estimated at 13.5 percent of the price per person. All this amounted to tens of billions of dollars during the antebellum period, with New Orleans as a prime beneficiary.

The Union captured New Orleans early in the American Civil War, sparing the city the destruction suffered by many other cities of the American South.

Twentieth century

A view across Uptown New Orleans, with the Central Business District in the background (1991).

A view across Uptown New Orleans, with the Central Business District in the background (1991).In the early 20th century, New Orleans was a progressive major city whose most portentous development was a drainage plan devised by engineer and inventor A. Baldwin Wood. Until then, urban development was largely limited to higher ground along natural river levees and bayous; Wood's pump system allowed the city to expand into low-lying areas. Over the 20th century, rapid subsidence, both natural and human-induced, left these newly populated areas several feet below sea level.

New Orleans was vulnerable to flooding even before the age of negative elevation. In the late 20th century, however, scientists and New Orleans residents gradually became aware of the city's increased vulnerability. In 1965, Hurricane Betsy killed dozens of residents, even though the majority of the city remained dry. The rain-induced 1995 flood demonstrated the weakness of the pumping system; since that time, measures were taken to repair New Orleans's hurricane defenses and restore pumping capacity .

Throughout the 20th Century, New Orleans experienced a significant drop in economic activity compared with newer southern cities such as Houston and Atlanta. While the port remains vitally important, automation and containerization resulted in fewer local jobs at the ports. Manufacturing in the city also diminished. New Orleans became increasingly dependent on tourism as an economic mainstay. Poor education and rising crime became increasingly problematic in the later decades of the century.

Geography

New Orleans is located at 29°57′53″N 90°4′14″W / 29.96472, -90.07056 (29.964722, −90.070556)[19] on the banks of the Mississippi River, approximately 105 miles (169 km) upriver from the Gulf of Mexico. According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 350.2 square miles (907 km2), of which 180.56 square miles (467.6 km2), or 51.55%, is land.

The city is located in the Mississippi River Delta on the east and west banks of the Mississippi River and south of Lake Pontchartrain. The area along the river is characterized by ridges and hollows.

Elevation of New Orleans

Elevation of New OrleansNew Orleans was originally settled on the natural levees or high ground along the Mississippi River. In fact, when the capital of French Louisiana was moved from Mobile, Alabama to New Orleans, the French colonial government cited New Orleans' inland location as one of the reasons for the move as it would be less vulnerable to hurricanes. After the Flood Control Act of 1965, the US Army Corps built floodwalls and man-made levees around a much larger geographic footprint that included previous marshland and swamp. Whether or not this human interference has caused subsidence is a topic of debate. A study by the Geological Society of America reported

“ While erosion and wetland loss are huge problems along Louisiana's coast, the basement 30 to 50 feet (15 m) beneath much of the Mississippi Delta has been highly stable for the past 8,000 years with negligible subsidence rates.”

On the other hand, a report by the American Society of Civil Engineers claims that "New Orleans is subsiding (sinking)":

“ Large portions of Orleans, St. Bernard, and Jefferson parishes are currently below sea level — and continue to sink. New Orleans is built on thousands of feet of soft sand, silt, and clay. Subsidence, or settling of the ground surface, occurs naturally due to the consolidation and oxidation of organic soils (called “marsh” in New Orleans) and local groundwater pumping. In the past, flooding and deposition of sediments from the Mississippi River counterbalanced the natural subsidence, leaving southeast Louisiana at or above sea level. However, due to major flood control structures being built upstream on the Mississippi River and levees being built around New Orleans, fresh layers of sediment are not replenishing the ground lost by subsidence. ”

Vertical cross-section of New Orleans, showing maximum levee height of 23 feet (7 m).

Vertical cross-section of New Orleans, showing maximum levee height of 23 feet (7 m).A recent study by Tulane and Xavier University notes that 51% of New Orleans is at or above sea level, with the more densely populated areas generally on higher ground. The average elevation of the city is currently between one and two feet (0.5 m) below sea level, with some portions of the city as high as 16 feet (5 m) at the base of the river levee in Uptown and others as low as 10 feet (3 m) below sea level in the farthest reaches of Eastern New Orleans.

In 2005, storm surge from Hurricane Katrina caused catastrophic failure of the federally designed and built levees, flooding 80% of the city. A report by the American Society of Civil Engineers says that "had the levees and floodwalls not failed and had the pump stations operated, nearly two-thirds of the deaths would not have occurred".

New Orleans has always had to consider the risk of hurricanes, but the risks are dramatically greater today due to coastal erosion from human interference. Since the beginning of the 20th century it has been estimated that Louisiana has lost 2,000 square miles (5,000 km2) of coast (including many of its barrier islands) which once protected New Orleans against storm surge. Following Hurricane Katrina, the Army Corps of Engineers has instituted massive levee repair and hurricane protection measures to protect the city.

In 2006, Louisiana voters overwhelmingly adopted an amendment to the state's constitution to dedicate all revenues from off shore drilling to restore Louisiana's eroding coast line. Congress has allocated $7 billion to bolster New Orleans' flood protection.

National protected areas:

Bayou Sauvage National Wildlife Refuge,

Bayou Sauvage National Wildlife Refuge is a 23,000 acre region of fresh and brackish marshes located within the city limits of New Orleans. It is the largest urban wildlife refuge in the United States.

Location,

Bayou Sauvage is only 15 minutes from the French Quarter. Most of the refuge is inside massive hurricane protection levees, built to hold back storm surges and maintain water levels in the low-lying city.

Wildlife,

An enormous wading bird rookery can be found in the swamps of the refuge from May until July, while tens of thousands of waterfowl winter in its marshes.

The brown pelican is an endangered species and is a year-round resident of southeast Louisiana. The number of nesting brown pelicans has substantially increased despite loss of nesting habitat. Brown pelicans are frequent users of the refuge. Several bald eagles, another threatened species, visit the refuge each year.

Other wildlife include waterfowl, wading birds, shorebirds, marsh rabbits, white pelicans, alligators, and other raptors, game and small mammals, reptiles and amphibians.

Habitat,

The refuge contains a variety of different habitats, including freshwater and brackish marshes, bottomland hardwood forests, lagoons, canals, borrow pits, chenieres (former beach fronts) and natural bayous. The marshes along Lakes Pontchartrain and Borgne serve as estuarine nurseries for various fish species, crabs and shrimp. Freshwater lagoons, bayous and ponds serve as production areas for largemouth bass, crappie, bluegill and catfish. The diverse habitats meet the needs of 340 bird species during various seasons of the year. Peak waterfowl populations of 75,000 use the wetland areas during the fall, winter, and early spring months.

Blue Crabs

Blue Crabs Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve (part),

Barataria Preserve

Barataria PreserveJean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve protects significant examples of the rich natural and cultural resources of Louisiana's Mississippi River Delta region. The park, named after Jean Lafitte, seeks to illustrate the influence of environment and history on the development of a unique regional culture. The park consists of six physically separate sites and a park headquarters.

Kenta Canal at Barataria Preserve, Louisiana

Kenta Canal at Barataria Preserve, LouisianaChalmette Monument and Grounds was established on March 4, 1907; transferred from the War Department to the National Park Service on August 10, 1933. It was redesignated Chalmette National Historical Park on August 10, 1939. Listed on the National Register of Historic Places on July 1, 1974. Chalmette was incorporated into a new park/preserve authorized on November 10, 1978.

New Orleans Jazz National Historical Park,

New Orleans Jazz National Historical Park is a U.S. National Historical Park in the Treme neighborhood of New Orleans, Louisiana, near the French Quarter. It was created in 1994 to celebrate the origins and evolution of jazz, America’s most widely-recognized indigenous music.

Perseverance Hall No. 4

Perseverance Hall No. 4The park consists of four acres within Louis Armstrong Park leased by the National Park Service. The park has an office, visitors center, and concert venue several blocks away in the French Quarter. It provides a setting to share the cultural history of the people and places that helped shape the development and progression of jazz in New Orleans. The park preserves information and resources associated with the origins and early development of jazz through interpretive techniques designed to educate and entertain.

Perseverance Hall No. 4,

The centerpiece of the site is Perseverance Hall No. 4 (not to be confused with Preservation Hall). Originally a Masonic Lodge, it was built between 1819 and 1820, making it the oldest Masonic temple in Louisiana.

Its historic significance is based on its use for dances, where black jazz performers and bands reportedly played for black or white audiences. Various organizations, both black and white, rented Perseverance Hall for dances, concerts, Monday night banquets, and recitals. Although the building was used for social functions, these uses have only been occasionally documented, perhaps[who?] because many pertinent Masonic records have been destryoyed.

Park sign at French Quarter visitors center.

Park sign at French Quarter visitors center.During the early 1900s some bands, such as the Golden Rule Band, were barred from appearing at Perseverance Hall, apparently because management considered them too unidignified for the place. The building also served as a terminal point for Labor Day parades involving white and black bands. During the 1920s and 1930s, well past the formative years of jazz, various jazz bands played there.

Perseverance Hall was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on October 2, 1973. The entire National Historical Park was administratively listed on the Register on the date of its authorizaton, October 31, 1994.

Cityscape,

The City of New Orleans & The Mississippi River

The City of New Orleans & The Mississippi RiverThe Central Business District of New Orleans is located immediately north and west of the Mississippi River, and was historically called the "American Quarter" or "American Sector." Most streets in this area fan out from a central point in the city. Major streets of the area include Canal Street, Poydras Street, Tulane Avenue and Loyola Avenue. Canal Street functions as the street which divides the traditional "downtown" area from the "uptown" area.

Bourbon Street, New Orleans, in 2003, looking towards Canal Street.

Bourbon Street, New Orleans, in 2003, looking towards Canal Street.Every street crossing Canal Street between the Mississippi River and Rampart Street, which is the northern edge of the French Quarter, has a different name for the "uptown" and "downtown" portions. For example, St. Charles Avenue, known for its street car line, is called Royal Street below Canal Street. Elsewhere in the city, Canal Street serves as the dividing point between the "South" and "North" portions of various streets. In the local parlance downtown means "downriver from Canal Street" while uptown means "upriver from Canal Street". Downtown neighborhoods include the French Quarter, Tremé, the 7th Ward, Faubourg-Marigny, Bywater (the Upper Ninth Ward), and the Lower Ninth Ward. Uptown neighborhoods include the Warehouse District, the Lower Garden District, the Garden District, the Irish Channel, the University District, Carrollton, Gert Town, Fontainebleau, and Broadmoor. However, the Warehouse and Central Business Districts, despite being above Canal Street, are frequently called "Downtown" as a specific region, as in the Downtown Development District.

New Orleans, Chartres Street looking towards Canal Street, (2004).

New Orleans, Chartres Street looking towards Canal Street, (2004).The Central Business District is a neighborhood of the city of New Orleans. A subdistrict of the French Quarter/CBD Area, its boundaries as defined by the City Planning Commission are: Iberville, Decatur and Canal Streets to the north, the Mississippi River to the east, the New Orleans Morial Convention Center, Julia and Magazine Streets and the Pontchartrain Expressway to the south and South Claiborne Avenue, Cleveland and South and North Derbigny Streets to the west. It is the equivalent of what many cities call their "downtown," although in New Orleans "downtown" or "down town" is often used to mean portions of the city in the direction of flow of the Mississippi River.

New Orleans Central Business District

New Orleans Central Business DistrictIberville Projects is a neighborhood of the city of New Orleans and one of the Housing Projects of New Orleans. A subdistrict of the Mid-City District Area, its boundaries as defined by the City Planning Commission are: St. Louis Street to the north, Basin Street to the east, Iberville Street to the south and North Claiborne Avenue to the west. It is located in the 4th Ward of downtown New Orleans on the former site of the famous Storyville district.

Iberville Projects on Basin Street

Iberville Projects on Basin StreetThe French Quarter, also known as Vieux Carré, is the oldest and most famous neighborhood in the city of New Orleans, Louisiana. When La Nouvelle Orléans ("New Orleans" in French) was founded in 1718 by Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville, the city was originally centered on the French Quarter, or the Vieux Carré ("Old Square" in French) as it was known then. While the area is still referred to as the Vieux Carré by some, it is more commonly known as the French Quarter today, or simply "The Quarter." The district as a whole is a National Historic Landmark, and it contains numerous individual historic buildings. It was relatively lightly affected by Hurricane Katrina in 2005. The Quarter is subdistrict of the French Quarter/CBD Area.

The French Quarter

The French QuarterLower Garden District is a neighborhood of the city of New Orleans. A subdistrict of the Central City/Garden District Area, its boundaries as defined by the City Planning Commission are: St. Charles Avenue, Felicity, Thalia, Magazine and Julia Streets to the north, the New Orleans Morial Convention Center, Crescent City Connection and Mississippi River to the east, Felicity, Magazine and Constance Streets, Jackson Avenue, Chippewa and Soraparu Streets to the south and 1st Street to the west.

Central City is a neighborhood of the city of New Orleans. It is located at the lower end of Uptown , just above the New Orleans Central Business District, on the "lakeside" of St. Charles Avenue. A subdistrict of the Central City/Garden District Area, its boundaries as defined by the City Planning Commission are: MLK Boulevard, South Claiborne Avenue and the Pontchartrain Expressway to the north, Magazine, Thalia, Prytania and Felicity Streets and St. Charles Avenue to the south and Toledano Street, Louisiana Avenue and Washington Avenue to the west.

This old predominantly African American neighborhood has been important in the city's brass band and Mardi Gras Indian traditions and includes three of the housing projects of New Orleans.

Gert Town (sometimes referred to as Zion City) is a neighborhood of the city of New Orleans. A subdistrict of the Mid-City District Area, its boundaries as defined by the City Planning Commission are: Palmetto Street, South Carrollton Avenue and the Pontchartrain Expressway to the north, South Broad Street to the east, MLK Boulevard, Washington Avenue, Eve Street, Jefferson Davis Parkway, Earhart Boulevard, Broadway and Colapissa Streets, South Carrollton Avenue and Fig Street to the south and Cambronne, Forshey, Joliet, and Edinburgh Streets to the west.

Broadmoor is a neighborhood of the city of New Orleans. A subdistrict of the Uptown/Carrolton Area, its boundaries as defined by the City Planning Commission are: Eve Street to the north, Washington Avenue and Toledano Street to the east, South Claiborne Avenue to the south, and Jefferson Avenue, South Rocheblave Street, Nashville Avenue, and Octavia Street to the west.

Broadmoor is low lying ground in New Orleans, and was only substantially developed beginning in the early 20th century after improved drainage was initiated (see: Drainage in New Orleans). Before being developed, the area was a large marsh and was a fishing spot for Uptowners. Early construction were mostly high raised houses for fear of repeats of historic floods, but after decades with little problem more low lying residential structures were built in Broadmoor.

Broadmoor resident musician and producer Dave Bartholomew named his Broadmoor Records label after the neighborhood.

Broadmoor was hit hard by the May 8th 1995 Louisiana Flood, after which extensive improvements of drainage were constructed.

Milan is a neighborhood of the city of New Orleans. A subdistrict of the Central City/Garden District Area, its boundaries as defined by the City Planning Commission are: South Claiborne Avenue to the north, Toledano Street and Louisiana Avenue to the east, St. Charles Avenue to the south and Napoleon Avenue to the west.

Freret is a neighborhood of the city of New Orleans. A subdistrict of the Uptown/Carrollton Area, its boundaries as defined by the City Planning Commission are: South Claiborne Avenue to the north, Napoleon Avenue to the east, LaSalle Street to the south and Jefferson Avenue to the west.

Uptown is a neighborhood of the city of New Orleans. A subdistrict of the Uptown/Carrollton Area, its boundaries as defined by the City Planning Commission are: LaSalle Street to the north, Napoleon Avenue to the east, Magazine Street to the south and Jefferson Avenue to the west.

Touro is a neighborhood of the city of New Orleans. A subdistrict of the Central City/Garden District Area, its boundaries as defined by the City Planning Commission are: St. Charles Avenue to the north, Toledano Street to the east, Magazine Street to the south and Napoleon Avenue to the west.

Garden District is a neighborhood of the city of New Orleans. A subdistrict of the Central City/Garden District Area, its boundaries as defined by the City Planning Commission are: St. Charles Avenue to the north, 1st Street to the east, Magazine Street to the south and Toledano Street to the west. The National Historic Landmark district extends a little further. The area was originally developed between 1832 to 1900. It may be one of the best preserved collection of historic southern mansions in the United States. The 19th century origins of the Garden District illustrate wealthy newcomers building opulent structures based upon the prosperity of New Orleans in that era. (National Trust, 2006)

Irish Channel is a neighborhood of the city of New Orleans. A subdistrict of the Central City/Garden District Area, its boundaries as defined by the City Planning Commission are: Tchoupitoulas, Toledano and Magazine Streets to the north, 1st Street to the east, the Mississippi River to the south and Napoleon Avenue to the west.

West Riverside is a neighborhood of the city of New Orleans. A subdistrict of the Uptown/Carrollton Area, its boundaries as defined by the City Planning Commission are: Magazine Street to the north, Napoleon Avenue to the east, the Mississippi River to the south and Exposition, Tchoupitoulas and Webster Streets to the west.

Audubon is a neighborhood of the city of New Orleans. A subdistrict of the Uptown/Carrolton Area, its boundaries as defined by the City Planning Commission are: South Claiborne Avenue to the north, Jefferson Avenue to the east, the Mississippi River and Magazine Street to the south, and Lowerline Street to the west. The name Audubon comes from Audubon Park, one of the largest parks in the city, which is located in the southern portion of the district. The area is also known as the "University District," as it is also home of Tulane and Loyola Universities, as well as the former St. Mary’s Dominican College (now a satellite campus of Loyola). The section of the neighborhood upriver from Audubon Park incorporates what was the town of Greenville, Louisiana until it was annexed to New Orleans in the 19th century; locals still sometimes call that area "Greenville".

Fontainebleau and Marlyville are jointly designated as a neighborhood of the city of New Orleans. A subdistrict of the Uptown/Carrollton Area, its boundaries as defined by the City Planning Commission are: Colapissa and Broadway Streets and MLK Boulevard to the north, South Jefferson Davis Parkway, Octavia Street, Fontainebleau Drive, Nashville Avenue, South Rocheblave, Robert and South Tonti Street and Jefferson Avenue to the east, South Claiborne Avenue, Lowerline and Spruce Streets to the south and South Carrollton Avenue to the west.

East Carrollton is a neighborhood of the city of New Orleans. A subdistrict of the Uptown/Carrollton Area, its boundaries as defined by the City Planning Commission are: Spruce Street to the northeast, Lowerline Street to the southeast, St. Charles Avenue to the southwest and South Carrollton Avenue to the northwest.

This was a portion of what was the city of Carrollton, Louisiana, before it was annexed to the city of New Orleans in the 19th century.

Landmarks include the Maple Street commercial district and Lusher School.

Black Pearl is a neighborhood of the city of New Orleans. A subdistrict of the Uptown/Carrollton Area, its boundaries as defined by the City Planning Commission are: South Carrollton Avenue and St. Charles Avenue to the north, Lowerline, Perrier and Broadway Streets to the east, and the Mississippi River to the west.

The name comes from the historically majority Black population and the name of "Pearl Street".

Most of the neighborhood is a section of what was the town of Carrollton, Louisiana in the 19th century; the designated neighborhood boundaries also include a portion downriver of Lowerline Street that was part of the town of Greenville. This later part includes "Uptown Square", a shopping mall complex more recently mostly converted to offices and residences.

This area on high ground escaped the Hurricane Katrina flooding suffered by most of the city in 2005. However a tornado strike in the early morning hours of February 13, 2007 did significant damage.

Leonidas (also known as West Carrollton) is a neighborhood of the city of New Orleans. A subdistrict of the Uptown/Carrollton Area, its boundaries as defined by the City Planning Commission are: South Claiborne Avenue, Leonidas and Fig Streets to the north, South Carrollton Avenue to the east, the Mississippi River and Jefferson Parish to the west.

The designated neighborhood incorporates the upper-river half of what had been the town of Carrollton, Louisiana in the 19th century. It is commonly known to locals as "Upper Carrollton" or "West Carrollton".

Hollygrove is a neighborhood of the city of New Orleans, located in the city's 17th Ward. A subdistrict of the Uptown/Carrollton Area, its boundaries as defined by the City Planning Commission are: Palmetto Street to the north, Cambronne, Edinburgh, Forshey, Fig and Leonidas Streets to the east, South Claiborne Avenue to the south and Jefferson Parish to the west.

The section closer to the Jefferson Parish line is sometimes known as "Pidgeon Town".

Lakewood is a neighborhood of the city of New Orleans. A subdistrict of the Lakeview District Area, its boundaries as defined by the City Planning Commission are: Veterans Memorial Boulevard to the north, Pontchartrain Boulevard and the Pontchartrain Expressway to the east, Last, Quince, Hamilton, Peach, Mistletoe, Dixon, Cherry and Palmetto Streets to the south and the 17th Street Canal to the west.

Mid-City is a neighborhood of the city of New Orleans. A subdistrict of the Mid-City District Area, its boundaries as defined by the City Planning Commission are: City Park Avenue, Toulouse Street, North Carrollton and Orleans Avenues, Bayou St. John and St. Louis Street to the north, North Broad Street to the east, and the Pontchartrain Expressway to the west. It is a historic district on the National Register of Historic Places. In common usage, a somewhat larger area surrounding these borders is often also referred to as part of Mid-City.

Tulane/Gravier is a neighborhood of the city of New Orleans. A subdistrict of the Mid-City District Area, its boundaries as defined by the City Planning Commission are: St. Louis Street to the north, North Claiborne Avenue, Iberville Street, North and South Derbigny Street, Cleveland Street, South Claiborne Avenue to the east, the Pontchartrain Expressway to the south and South Broad Street to the west.

Tremé (historically sometimes called Tremé or Faubourg Tremé or Tremé/Lafitte when including the Lafitte Projects) is a neighborhood of the city of New Orleans. A subdistrict of the Mid-City District Area, its boundaries as defined by the City Planning Commission are: Esplanade Avenue to the north, North Rampart Street to the east, St. Louis Street to the south and North Broad Street to the west. It is one of the oldest neighborhoods in the city, and early in the city's history was the main neighborhood of free people of color. It remains an important center of the city's African-American and Créole culture, especially the modern brass band tradition.

Landmarks in the area include St. Joseph's Church, University Hospital, the Deutsches Haus, and the Falstaff and Dixie Breweries (both now closed).

Bayou St. John is a neighborhood of the city of New Orleans. A subdistrict of the Mid-City District Area, its boundaries as defined by the City Planning Commission are: Esplanade Avenue to the north, North Broad Street to the east, St. Louis Street to the south and Bayou St. John to the west.

Fairgrounds is a neighborhood of the city of New Orleans. A subdistrict of the Mid-City District Area, its boundaries as defined by the City Planning Commission are: Florida Avenue, Dugue, Treasure, Republic and Abundance Streets to the north, North Broad Street to the east, Esplanade Avenue to the south and Bayou St. John to the west.

St. Bernard Projects is a neighborhood of the city of New Orleans and one of the Housing Projects of New Orleans. A subdistrict of the Mid-City District Area, its boundaries as defined by the City Planning Commission are: Harrison Avenue to the north, Paris Avenue to the east, Lafreniere Street and Florida Avenue to the south and Bayou St. John to the west.

Filmore is a neighborhood of the city of New Orleans. A subdistrict of the Gentilly District Area, its boundaries as defined by the City Planning Commission are: Robert E. Lee Boulevard to the north, London Avenue Canal to the east, Press Drive, Paris Avenue and Harrison Avenue to the south and Bayou St. John to the west.

Lake Terrace/Lake Oaks is a neighborhood of the city of New Orleans. A subdistrict of the Gentilly District Area, its boundaries as defined by the City Planning Commission are: Lake Pontchartrain to the north, the Industrial Canal to the east, Leon C. Simon Drive, Elysian Fields Avenue, New York Street, the London Avenue Canal and Robert E. Lee Boulevard to the south and Bayou St. John to the west. The neighborhood comprises the Lake Terrace and Lake Oaks subdivisions and the University of New Orleans, all built on land reclaimed from Lake Pontchartrain.

Pontchartrain Park is a neighborhood of the city of New Orleans. A subdistrict of the Gentilly District Area, its boundaries as defined by the City Planning Commission are: Leon C. Simon Drive to the north, the Industrial Canal to the east, Dreux Avenue to the south and People's Avenue to the west.

Landmarks in the neighborhood include the Carrollton Streetcar Barn, Palmer Park, the Water Works, and the Oak Street commercial district including the well known Maple Leaf Bar.

Other major districts within the city include Bayou St. John, Mid-City, Gentilly, Lakeview, Lakefront, New Orleans East, and Algiers.