George Beulah Tann (Georgia)

The sinister story of the woman who stole children and sold them to the stars

The baby snatcher: Georgia Tann stole children from their real families and sold them for her own profit

As she watched her baby coughing in her cot in a corner of her tiny apartment, Alma Sipple felt increasingly desperate.

A single mother in Tennessee, she could not afford medical care for

ten-month-old Irma. Suddenly, a knock on the door heralded a turn in her

fate: there stood a woman with close-cropped grey hair, round wireless

glasses and a stern air.

She exuded authority as she

explained she was the director of a local orphanage and had come to

help. Alma rushed to show the lady her sickly child.

Examining

the baby, the woman offered to pass her off as her own at the local

hospital in order to obtain free treatment. She warned Alma not to

accompany her, explaining: 'If the nurses know you're the mother,

they'll charge you.'

Lifting the child from the cot, the woman turned on her heel and disappeared. Two days later, Alma was told her baby had died.

In fact, Irma had been flown to an adoptive home in Ohio. Alma would not see her daughter again for 45 years.

For far from being her saviour, the woman who had taken Irma was a baby thief.

For

30 years, Georgia Tann made millions selling children. A network of

scouts, corrupt judges and politicians helped her steal babies. She also

targeted youngsters on their way home from school, promising them ice

cream to tempt them away from their homes.

Legal papers would be signed saying they were abandoned - most would never see their families again.

Now,

her story has been revealed in a new book. After painstakingly

contacting her surviving victims and a forensic search through the

archives, Barbara Bisantz Raymond calculates that Tann sold more than

5,000 children - and killed scores through neglect.

During the time she ran her 'business', the infant mortality rate in Memphis was the highest in the country.

Tann molested some of the girls in her care and placed children with paedophiles.

She charged fees to couples desperate to be parents

Some

victims were sold as underage farm hands or domestic skivvies. Others

were starved, beaten and raped. The lucky ones were sold to wealthy

parents, with Hollywood stars, including Lana Turner and Joan Crawford -

who adopted twins Cathy and Cynthia - lining up for babies.

Some of the children were featured in magazine articles. A number were placed with families in Britain.

So, who was Georgia Tann and how did she come to ruin so many lives?

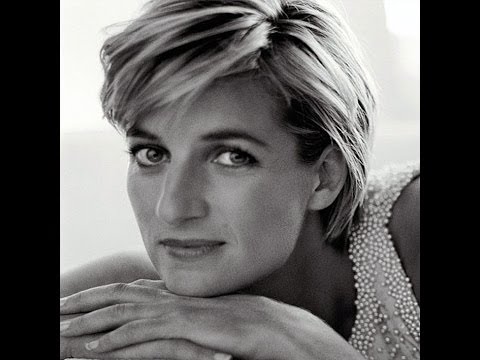

Born

in Hickory, Mississippi, in 1891, her father, George, was a high court

judge and her mother, Beulah, a Southern belle. Inside their lavish

house, all was not well.

Sold: Joan Crawford with her adopted daughters Cathy and Cynthia. Many other victims of Georgia were not so lucky

Tann's

father was an arrogant, domineering womaniser. From an early age, it

became clear Georgia was a disappointment to her strait-laced parents.

Big-boned and broad-shouldered, she wore flannel shirts and trousers:

unacceptable clothing for a woman at the time. A car accident had left

her with a limp.

Social work was one of the few acceptable

careers for women of Tann's class, and despite having no empathy with

the vulnerable, she saw it as an escape route from her staid home.

She

developed her own theories on society. In eugenic language which would

be echoed to infamous effect in Nazi Germany, she described wealthy

people as 'of the higher type'.

She

considered the poverty stricken young women left in poverty by the

Depression as 'breeders', privately referring to them as 'cows'. She

argued that poor people were incapable of proper parenting.

After getting a job at the Mississippi Children's Home-Finding Society, she began to translate her beliefs into action.

At the time, adoption was uncommon in the USA. Tann would change that.

At

first, she simply placed orphans for adoption. But soon, she realised

she could make money by charging hefty fees to couples desperate to

become parents.

Mothers were falsely told their newborn had died

By

1920, exploiting the lack of regulations on adoption and her father's

position as a judge, Tann began placing children she had kidnapped from

poor women.

One of the first mothers she

targeted was Rose Harvey. One spring morning in 1922, Tann drove her

Ford Model T to a cabin in Jasper County, Mississippi.

Asleep

inside was pregnant Rose, who was young, poor, widowed and suffering

from diabetes. Her two-year-old son, Onyx, was playing on the back

porch.

Tann lured the sturdy, black-haired, brown-eyed boy

into her car. Her father signed legal papers declaring Rose to be an

unfit mother and Onyx an abandoned child. He was placed with an adoptive

family. Rose engaged a lawyer, but was unable to regain custody.

In

1924, Tann started work at the Tennessee Children's Home Society, where

she turned part-time baby snatching into big business.

'I

can still hear her steps down the hallway. She had big feet and wore

black lace-up shoes,' says a former resident at the children's home.

'She always went upstairs to see the babies. There would be masses of them one day. They'd be gone the next.'

Wealthy parent: Lana Turner, pictured in the

film Another Time, Another Place, was another Hollywood actress to adopt

a child through Georgia

Tann acquired the protection of

Memphis's corrupt and all powerful mayor, Edward Hull Crump, and

eventually set up her own orphanage, at 1556 Poplar Avenue.

By

then, she had met her lesbian partner, Ann Atwood Hollinsworth, who

helped Tann ferry babies around the country - as far from their natural

parents as possible.

Tann adopted a daughter, June, in 1922.

June's daughter, Vicci, says: 'Mother said Georgia Tann was a cold fish;

she gave her material things, but nothing else. I don't know why she

bothered to adopt her.'

By the Thirties, Tann was charging

wealthy couples up to £100,000 in today's money for babies. So, how did

she arrange a steady flow of children she could sell?

In some

cases, single parents would drop off their children at nursery - when

they came back to collect them, they would be told they had been taken

away by welfare officers.

Tann offered accommodation to

children whose parents were in trouble and targeted the most beautiful

infants she could find, dressing them in lace outfits to meet

prospective clients.

Older children would be instructed to 'sit on that man's lap and call him daddy'.

Newborns were most in demand. Tann bribed maternity hospital nurses, who falsely told mothers their babies had died.

Irene

Green remembers being told her baby was stillborn. 'But I heard him

cry!' she protested. She asked to see the body, but was told it had been

'disposed of'. In fact, Georgia's workers had snatched the child.

Tann would falsify birth certificates

Mary

Reed was a typical victim. In 1943, aged 18, she gave birth to a baby

boy. She was barely conscious when she was presented with a 'routine

paper' to sign by a woman dressed in white.

By the time Mary came round and asked for her baby, the child was in New Jersey.

She

hired a lawyer but never got her child back. Tann would alter the

children's records and falsify birth certificates to make them more

appealing to prospective adopters.

Their mother would be

described as 'the daughter of a doctor' who had fallen pregnant

accidentally, while the father would be 'a medical student'.

She knocked years off the children's age, so they appeared precocious - and to stop them being traced.

Some

youngsters were accused of disappointing their adoptive families. Joy

Barner was told as a teenager by her father: 'I paid 500 dollars for you

- I could have gotten a good hunting dog for a lot less. You come from

the lowest scum on earth.'

She later found out she had been stolen in 1925 from a loving family living on a houseboat.

Many of the children were abused. Jim Lambert and his three siblings were taken from their mother by Tann in 1932.

Adoption remains popular in Hollywood: Brad Pitt

and Angelina Jolie have adopted three children but thankfully evil

Georgia is no longer around to organise the placements

The Chicago couple he was placed with divorced and Jim's stepmother hung him up from a hook in the basement.

He

and his siblings eventually traced their birth mother, only to find she

had died. In her Bible, beside the names of her stolen family she had

written: 'The children of a brokenhearted mother. I have no one to love

me now.'

He later said: 'I feel angry, frustrated, as if I was cheated out of a whole lot of life.'

Billy Hale recalled being driven away from his mother, crying, in a limousine, with two women in black.

His loving adoptive parents repeatedly reassured him no such event had occurred.

Through

his childhood, he suffered from seemingly motiveless rages. It was only

many years later, when he researched his background, that he realised

his memory was correct.

He tracked down his mother, Mollie,

only to be told by her brother she had died of cancer eight years

previously, calling out for her son at the end.

He was told: 'She looked for you all her life, Bill.'

'She was a relentless, cold-blooded demon'

By

1935, Tann had placed children in every U.S. state. A social worker who

knew her says: 'She placed with no regard to whether children would be

happy in their adoptive homes. She wanted to get her hands on every

child she could.'

Among the most disturbing cases are the

adoptions by single men of young teenagers - Bisantz Raymond suspects

they were paedophiles.

Keen to make more money, Tann began

running 'Georgia's Christmas Baby Ads' in the local newspaper under the

headline: 'Want a real, live Christmas present?'

A brilliant

publicist, she gave lectures on adoption, arguing that adopted children

'turn out better' than birth children, saying: 'Ours is a selective

process. We select the child and we select the home.'

She was lauded in the national Press as 'the foremost leading light in adoption laws'.

Eleanor Roosevelt sought her counsel regarding child welfare, and President Truman invited her to his inauguration.

But by 1940, alerted by the rising infant mortality rate in the city, some people were on to Tann.

'She

was a relentless, cold-blooded demon,' says a paediatrician who tried

to curb her. 'She got bigger and bigger the more power she had. She was

pompous and self-important, riding around in a Cadillac driven by a

uniformed chauffeur. She terrorised everyone.'

By 1950,

officials began a long-overdue investigation into Tann's business. State

investigator Robert Taylor reported the horror of what had taken place

at Tann's orphanage, saying: 'Her babies died like flies.'

Infants

were kept in appalling conditions in suffocating heat. Some were

sedated until they could be sold. Many were ill. Some were sexually

abused - Tann preyed on young girls and a male caretaker would take

little boys into the woods.

A news reporter believed he saw a body being buried in the garden.

In 1945, a bout of dysentery caused the deaths of between 40 and 50 children in less than four months.

The damage suffered at Tann's hands could never be undone

The

net was closing, but Tann would evade justice. Three days before her

death due to cancer, the governor of Tennessee revealed at a press

conference that Tann was not the 'angel of adoption' she claimed to be.

He

did not mention the grieving parents or dead babies, but focused on the

illegal profits she had made while receiving state funding.

Conveniently

for the corrupt politicians who had collaborated in her black market

baby trade, Tann was too sick to be questioned about her crimes. She

died in her four-poster bed at 4.20am on September 15, 1950.

What

became of her victims? Many never saw their families again - after

Tann's crimes came to light, there was no attempt to return children to

their rightful homes.

They were granted rights to their birth

certificates and adoption records only in 1995, after a long battle. A

small number were reunited with their birth mothers, but the damage they

had suffered at Tann's hands could never be undone.

Forty-five

years after Tann had walked into her apartment, Alma Sipple finally

found Irma, but they were unable to form a lasting relationship.

'Only

someone who has lost a child this way can know how horrible it is,'

says Alma. 'There's a hole in my heart that will never be filled.'

Camille Kelley, Judge of the Shelby County Juvenile Court, 1940

Camille Kelley, Judge of the Shelby County Juvenile Court, 1940